The rationale for this blog portfolio is to track the development of my research interests and my personal growth as a potential academic throughout the year as part of the MA module: “Contemporary Literary Research: Skills, Methods and Strategies”.

I was fortunate enough to have prior experience in academic and commercial blogging. One of the requirements for my undergraduate “Children’s Literature” seminar was to contribute weekly posts to a group blog responding to the texts that were being studied each week. I enjoyed this aspect of the seminar so much that I sought out voluntary blogging experience by writing short, concise, consumer targeted blog posts for Strategy Internet Marketing. This was a brief but invaluable experience as it introduced me to the important issue of image copyright and taught me how to locate and reference images that were free to use commercially. There were also disadvantages with these experiences, while I had gained experience in writing for two different audiences; there were no accompanying editorial duties with either. This blog would be the first time that I would have editorial responsibility over my own posts and also provided me with experience in maintaining my own webpage.

Despite my previous experience, I am disappointed with my earlier blog posts because while they were academic and scholarly pieces they had little personal input and reflection. My first post on Caedmon’s Hymn is a clear example of this:

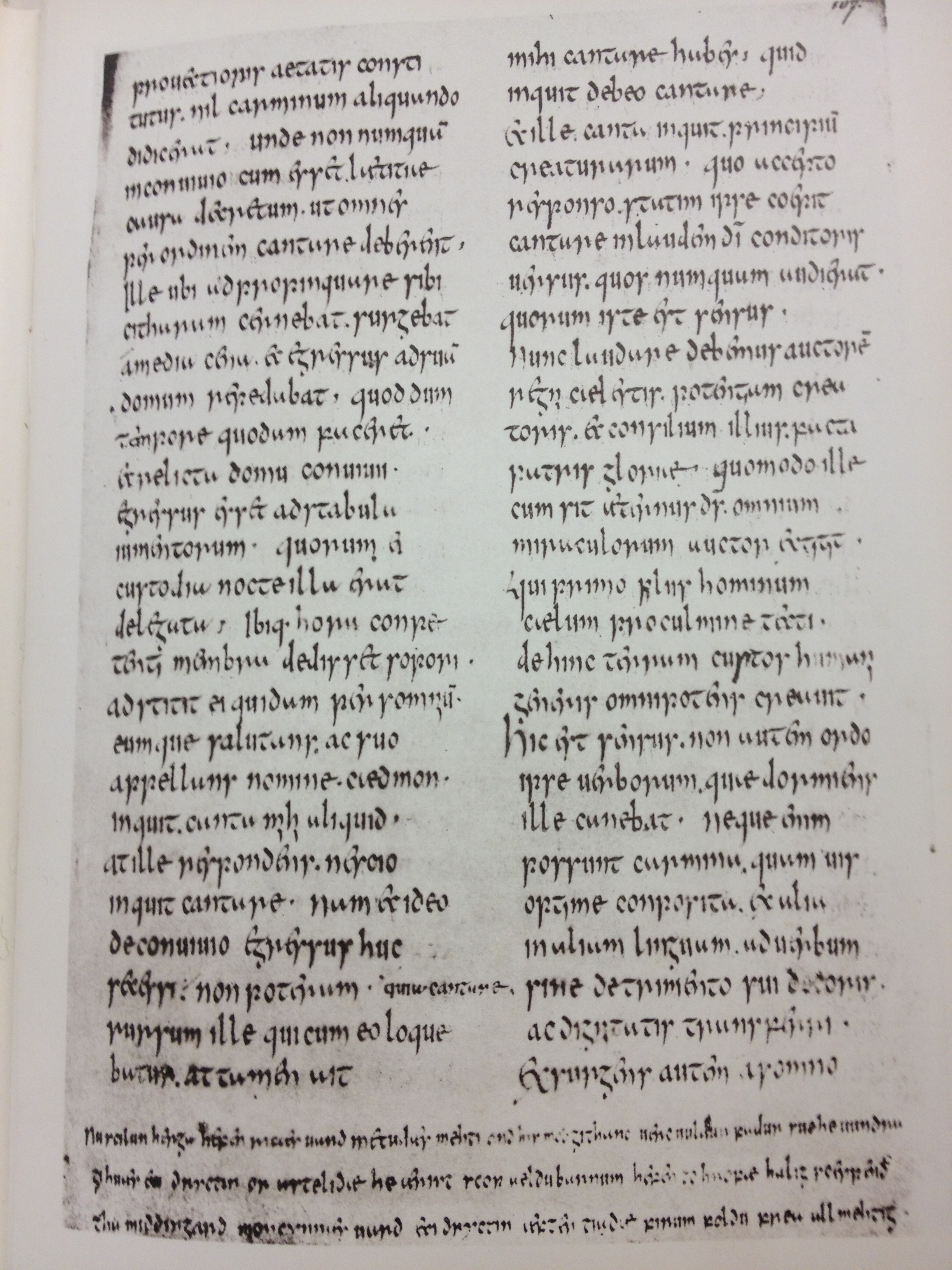

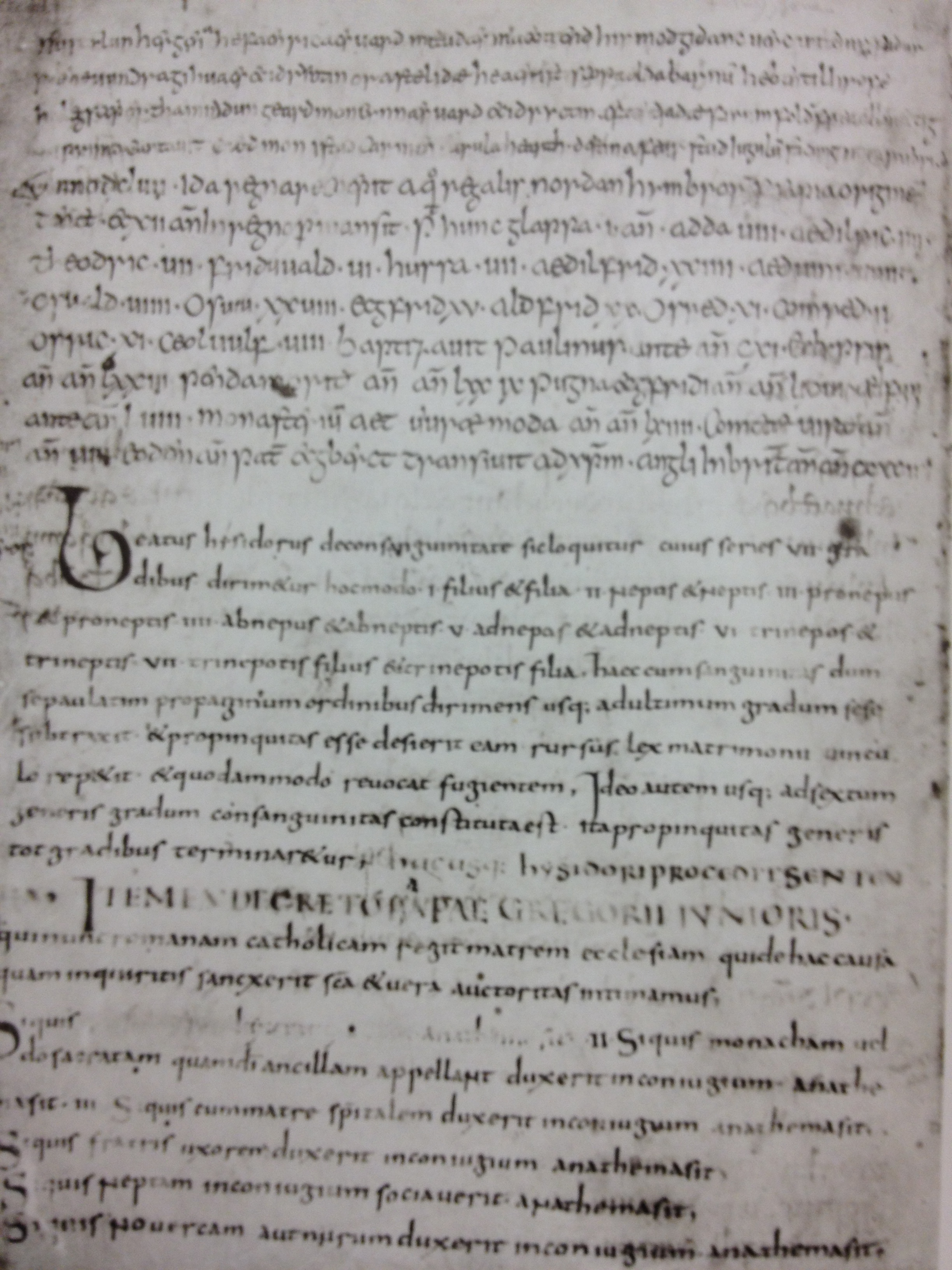

“Manuscript Witnesses.

Fortunately, I had the opportunity to track the history of Caedmon’s Hymn by examining facsimiles of its different manuscript witnesses. I have included below a brief summary detailing my first encounter with facsimiles.

- “The Leningrad Bede” St. Petersburg, Russian National Library Lat. Q.v.I.18 [Gneuss 846]

- “The Moore Bede” Cambridge, University Library Kk.5.16 [Gneuss 25]

- “The Tanner Bede” Oxford Bodleian Library Tanner 10(9830) [Gneuss 668]

“The Leningrad Bede”

Looking first at the eighth century “Leningrad” witness, the Hymn appears as a marginal gloss on the bottom of the manuscript. On examining this manuscript I could clearly distinguish between the smaller grade insular used for the vernacular version of Caedmon’s Hymn and the larger grade insular minuscule reserved for the central text.

Another important factor distinguishing the Latin and Vernacular versions is the layout. In the picture of the facsimile provided below one can clearly see that the vernacular translation runs in a continuous line across the bottom of the manuscript, while the central text above is laid out in separate columns.

“The Moore Bede”

The second eighth century witness, “The Moore Bede”, shows the Hymn as marginal gloss on the top of the manuscript. I found it more difficult to distinguish between the vernacular version and the central text in this particular manuscript as it was in closer proximity to the central text.

From the picture below it’s clear that in this manuscript witness, the layout of both the Latin and the vernacular incorporated the continuous line structure. In this instance distinguishing between the Latin and vernacular text would rely on my novice ability to either spot the different grades of insular minuscule, or to decipher the words before me until I found a familiar Old English word.

“The Tanner Bede”

The third manuscript witness dated from the early eleventh century and shows the vernacular version of Caedmon’s Hymn occupying its place of prominence as the central text of the manuscript. Now that Caedmon’s Hymn occupied the centre of the manuscript I found it more difficult to distinguish it apart from the surrounding text. In this particular manuscript witness there was no difference in terms of layout or grade of script to indicate the beginning of the Hymn; this time I had to read through the manuscript until I met the Hymn‘s famous opening word “Nu” before I could find it.”

This excerpt from my first blog post is disappointing for one principal reason; it does not convey the excitement that I felt in engaging with the facsimiles for the first time in Special Collections. I found studying the manuscript witnesses of Caedmon’s Hymn exciting because I could clearly see the evolution of the vernacular language within manuscript culture. My post on my favourite Old English poem The Battle of Maldon: The Crisis within the Comitatus shared a similar fate:

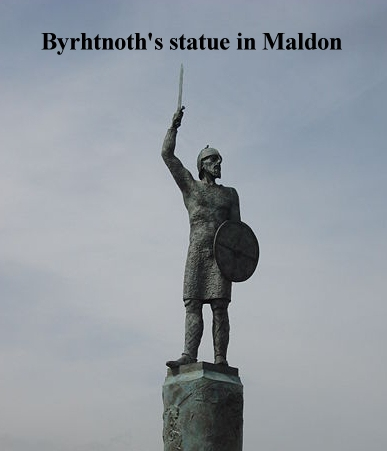

“The Crisis

Contrary to what one might expect the central conflict in The Battle of Maldon isn’t between the Vikings and the English. In fact the Maldon poet simply uses the Vikings as an impetus to emphasize the real crisis; the disintegration of the comitatus and its inherent heroic code of behaviour. As Frank and Clark adroitly articulate the central theme in Maldon is loyalty, and the moral battle between “heroism and cowardice” is evident throughout the poem (Frank; Clark 58).

Tolkien was evidently aware of this theme and he skilfully appropriated it into his own work. The influence of The Battle of Maldon on Aragorn’s speech at the Black Gate is evidently great, and his explicit reference to the breaking of the bonds of fellowship vocalises the implicit moral conflict amongst the English forces at Maldon.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1jG1bity2E]

Glory Motif

Heroic literature perpetuates the heroic code of behaviour by promoting glorious and honourable deaths in battle over instinctual survival. This drive of fighting for fame is so explicit in The Battle of Maldon that the poem has been regarded as one of the best expressions of the heroic ideal in Anglo Saxon literature. Its powerful influence can still be felt by a modern audience after an interlude of hundreds of years.

In this second scene Tolkien uses Theoden (The Old English word for lord or leader) as a substitute for Byrhtnoth. In this instance Tolkien vocalises the heroes’ desire for an honourable and glorious death in battle through the Rohirrim’s charging to the word “death”.

Fight or Flight?

How The Battle of Maldon achieved its high status is down to the poet’s stylistic choice to deliberately juxtapose the heroic ideal with the flight of the cowards. This juxtaposition allows the audience to see that The Battle of Maldon is essentially a test of character as Ælfwine remarks himselfat line (215) “nu mæg cunnian hwa cene sy”, now it will be tested who is brave.

There’s a distinct tone of disapproval throughout the flight of the cowards event that can be encapsulated in the words “hit riht ne wæs” (190). This is clearly felt in the poet’s description of Godric’s abandonment of his beloved lord: “Godric fram guþe, and þone godan forlet þe him mænigne oft mear gesealde…þe hit riht ne wæs” (187-190) and the beot or the heroic and boasting words that were spoken before battle are left unfulfilled in the time of need: “þa he gemot hæfde, þæt þær modelice manega spræcon þe eft æt þearfe þolian noldon” (199-200).

The poet’s allegiance is clearly with the heroes who stayed and fought. The repetitive nature of speeches after the flight of the cowards suggests that their rationale is to reinforce this heroic code of behaviour. Byrhtwold, the aged retainer and kinsman of the deceased leader Byrhtnoth, reminds the younger thanes of their duty after the flight of the cowards: “fram ic ne wille, ac ic me be healfe minum hlaforde…licgan þence” 317-318). After the cowards flee and the obvious hero Byrhtnoth dies, the poet focuses their attention on the words and actions of the men who fulfilled their oath and their beot: “Þa ðær wendon forð wlance þegenas, unearge men….hi woldan þa ealle oðer twega, lif forlætan oððe leofne gewrecan” (205-208).”

While this blog post held little personal reflection I am very happy with my effective use of the different media options offered by the WordPress website. I purposefully used the different media to create an interactive and engaging reading experience by breaking up the text with relevant visuals. I felt that my decision to include the different media was effective because I received a long in-depth comment responding to this post which boosted my confidence in my own blogging ability.

The Christmas holidays provided an opportunity to review my progress to date. It was at this point that I realised that my posts had little personal reflection and that the module “New Histories of the Book” was continually exciting my interest. This module had inspired several posts such as:

- Palaeography: An Introduction,

- Victorian Gift Books and Manuscript Culture,

- Reconciling the Old English “Apollonius of Tyre” with its Manuscript Context: The Miscellany CCCC201 and

- The juxtaposition of the lofty “Knyghtes Tale” with the rude “Myllers Tale”.

This codicological and palaeographical interest was evident from my very first post where I discussed examining the facsimiles of Caedmon’s Hymn and would continue to inspire future posts, which leads me to my post on my Book History assignment – The Trials and Tribulations in Producing an Edition:

“Assessment is an inescapable aspect of all MA courses and usually involves the submission of an essay for your selected modules. Suffice it to say that as an English Literature student at MA level, I’m well acquainted with essays. So I wasn’t surprised when I was immediately attracted to the assessment topics provided by The New Histories of the Book module belonging to the Medieval to Renaissance Literature MA. Two of these assessment topics in particular offered an exciting opportunity to attempt something new; to provide an in-depth manuscript description or to produce a mini edition of the opening lines to one of Aelfric’s Catholic Homilies from Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 178.

My interest in transcribing swiftly drew me to the latter question. My preliminary research into CCCC178 determined that it’s a manuscript comprised of two parts. The first part, which would be the main focus of my essay, was possibly compiled in the early eleventh century and contains Aelfric’s Catholic Homilies. The second part of this codex preserves a Latin and Old English version of “The Rule of Saint Benedict”.

The Criteria for the Mini Edition

My initial excitement was quickly accompanied by anxiety once I realised that in order to complete this assessment successfully, I would have to address specific criteria that required me to: include an Introduction outlining my editorial principles, a text that included explanatory notes on any variants in my edition as well as a critical apparatus.

Considering that I was ignorant of editorial principles and oblivious to what a critical apparatus entailed I was understandably a little overwhelmed.

Helpful Potential Sources

The surest way of overcoming your fears is to face them. To acquaint myself with and get a comprehensive idea of what I should be aspiring towards in my own edition I sought out the following sources from the Boole Library’s Special Collections:

- The Facsimile of Aelfric’s First Series of Catholic Homilies.

- Aelfric’s Catholic Homilies: The First Series edited by Peter Clemoes.

- Aelfric’s Catholic Homilies: Introduction, Commentary and Glossary by Malcolm Godden.

Essentially my hope in consulting these established editions was to become accustomed to what’s expected of me in relation to stating editorial principles and critical apparatus.

Manuscript Witnesses

In addition to the aforementioned criteria I had to consult three different manuscript witnesses of the homily that I selected. In keeping with the festive season (the assessment was to be completed over the Christmas Holidays) I decided upon “The Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ” from Aelfric’s First Series of Catholic Homilies.

Now all I had to do was select just three manuscript witnesses of this Homily from the abundance of manuscript witnesses to Aelfric’s Catholic Homilies! Easy? Evidently not! I quickly realised that although Aelfric was a prolific homilist, access to his abundant manuscripts was more difficult than I had initially anticipated. Fortunately I had at my disposal in the Boole Library’s Special Collections, a Facsimile edition of Aelfric’s First Series of Catholic Homilies. For the other two witnesses my decision was restricted to those manuscripts that were accessible online. The manuscripts that I selected to complement CCCC 178 were:

- British Museum, Royal 7 C XII

- Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 188

- Cambridge University Library, Ii. I. 33

Free and Open Access

The importance of open and free access to resources for academic research has been stressed throughout the Contemporary Literary Research module that complements this MA. This assessment heightened my awareness of its importance especially in relation to accessing manuscripts online. The Parker Library on the Web and the Cambridge Digital Library were indispensable in the production of this edition as it allowed me to access CCCC178 and CCCC188 and CUL Ii. I. 33.

The only issue left to overcome were the considerable amount of marginal and interlinear glosses preserved in CCCC178 which I couldn’t decipher with the basic view offered by The Parker Library on the Web. Being but a poor and humble student I couldn’t afford the subscription that provided zoom function to focus on the smaller grade script, but after explaining my predicament via email I was informed that I could purchase the images that included the zoom function from the Library.

Conclusion

This assessment required many hours spent within the confines of Special Collections, and while it hasn’t resulted in a first name basis with the Librarians, I’m sure that my pending MA dissertation will guarantee it. To conclude on a more serious note, I’m glad that I opted for producing this mini edition over a standard essay. I found the experience engaging, challenging and thoroughly rewarding. I only hope that my elusive MA dissertation will yield equally auspicious results!”

This post is pivotal because it shows a progression in my writing style and research interests. My posts after Christmas show a decisive shift into a more personal reflective writing style. I found writing in this style was a more fluid and enjoyable experience and I think this resulted in my posts becoming more inviting and engaging. In respect to my personal development as an academic I was surprised by my own increasing awareness of academic issues; namely, the importance of free and open access within the research community. I am satisfied with how my blog showed my research interest evolving into a palaeography based assessment. My post Should we judge books by their covers? was inspired by visiting scholar Dr David Rundle from the Centre for Bibliographical History, University of Essex, and confirmed that this burgeoning interest could be a potential thesis topic:

“Last week I was faced with a very difficult decision, to go see the new Lego Movie or attend a lecture given by Dr David Rundle entitled “The Uses of Books in Late Medieval Culture”? Fortunately for you, I chose the latter and was rewarded handsomely! Within the space of an hour this erudite lecturer ruminated upon the fact that within medieval culture a book was not solely reading material but an object that within a specific moment had its own agency.

This specific moment is the presentation of the book itself. The book had agency in the presentation event because it created a social opportunity for both its producer and its royal recipient. For the producer of the book the presentation was an opportunity for patronage, and in accepting the book the recipient would have to show their largesse.

During this lecture I was struck by the fact that the content of the books were not fully recognised. While the significance of the book was widely acknowledged in medieval culture, literate people formed the minority within a culture dominated by illiteracy. Therefore the potential to fully engage with writing and realise the significance of a book’s content was reserved for those elite few who could both read and write.

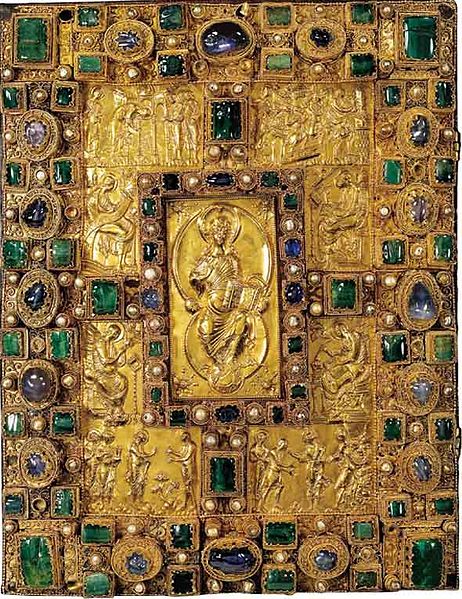

In his lecture Dr Rundle used certain manuscript illuminations depicting book presentation events as visual aids to further elaborate this fact. These illuminations usually involved an open book, with the presenter in a reverential kneeling position and the royal recipient ruminating upon the book’s content. The illuminations that I found particularly interesting were the ones that depicted a closed book being presented. In these representations it was clear that it was the book’s luxurious binding was the focus in their presentation.

One of Dr Rundle’s visual aids was a manuscript illumination depicting Christine de Pisan presenting her expensively bound and decorated book to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria. Within this context it is clear that reading is not a book’s sole purpose. A book was also a means of demonstrating a person’s continuing social status which subsequently stimulated the development of more deluxe and luxurious forms of book binding, such as Treasure binding.

The “New Histories of the Book” module of the Texts and Contexts: Medieval to Renaissance MA in University College Cork introduced the notion that a book’s paratext, the extraneous elements of the book, are just as important as its content in understanding its context. Dr Rundle’s talk complemented this module by dwelling upon the book’s connection to social status within a medieval context. To conclude, when faced with a book as lavishly decorated and bound as the Codex Aureus of St Emmeram, how do you not judge the book by its cover?

For those who wish for superior discussions about palaeography or codicology, visit Dr David Rundle’s WordPress Blog!”

This post attests that maintaining this blog has been an invaluable opportunity to develop my research interest in tandem with established academics. Similarly my posts written in response to the School of English Research Seminars, Victorian Gift Books and Manuscript Culture and Emmerich’s Reimagining of Elizabeth I in “Anonymous”, helped me form connections and links between my own studies and post doctoral research.

In conclusion, I found maintaining this blog to be an enjoyable and rewarding learning process. Throughout the year I made an concerted effort to contribute regular blog posts and I effectively exploited the available media features to compliment my blog:

- I succeeded in disseminating my research via social media by linking my blog to my academic twitter account.

- I used the hyperlink feature to incorporate relevant videos into my posts or to link to WordPress blogs belonging to referenced academics.

- In my review Textualities Conference 2014 I included visuals such as images and gifs and tweets from the day.

Personally this year has been characterised by trepidations regarding my impending thesis, contributing to this blog has done much to assuage these anxieties. Ultimately Brimwylfes mere has been an indispensable resource for monitoring the evolution of my thesis direction; it was only after receiving feedback from my blog mentor in preparation for this reflective journal that I realised I had unconsciously been focusing on this area all along.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

essayforme

April 1, 2018 at 7:00 pmdo my essay for me http://sertyumnt.com/

My brother suggested I might like this blog. He was totally right. This post actually made my day. You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for this information! Thanks!

writeessay

April 11, 2018 at 3:00 pmdo an essay for me http://dekrtyuijg.com/

Thanks! I enjoy this!