Introduction

The beginning of this MA coincided with exploring the importance of Caedmon’s Hymn in relation to the miraculous origin of Old English literature. According to Bede, Caedmon was an illiterate cowherd who had a divine vision one night and awoke the next day with the ability to compose Christian verses adhering to the metrical form of vernacular oral poetry (Shepherd 120).

Why Latin?

Bede recorded this miraculous event in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People with a detailed account of what occurred prior, during and after Caedmon’s heavenly encounter; but instead of recording Caedmon’s eponymous Hymn in the English language, Bede chose to represent the Hymn by paraphrasing it in Latin (Kiernan 158). Bede’s decision to paraphrase the Hymn in Latin offers invaluable insight into the cultural context of his Ecclesiastical History and the English language during this period. In compiling his Ecclesiastical History Bede’s intention was to portray a unified Christian community or nation; including Caedmon’s Hymn as a Latin paraphrase was the best way to achieve this propaganda as all texts of importance at this time, had been written in Latin. The significance of this decision in light of the English language, is that it highlights that Old English was considered as belonging to the oral and pre-Christian world. Furthermore, as a language Old English consisted of different dialects for example, West Saxon and Northumbrian, a factor that would undoubtedly have complicated his portrayal of the English as a collective identity.

Towards the Vernacular

The earliest evidence of vernacular recordings of Caedmon’s Hymn appear in the eighth century in the form of marginal glosses, which were written in a smaller grade of the insular minuscule that was used for the recording the main text (Kiernan 163). The different grades in the scripts help to distinguish the vernacular translation from the central text, Bede’s Latin paraphrase; which was written in the larger grade, serves as a clear indication of its prominence. It isn’t until the tenth century, as a result of King Alfred’s educational reforms, that a vernacular version of Caedmon’s Hymn appears as the central text within a manuscript. Indeed, it is thanks to the efforts of a creative scholar, who composed the Hymn following Bede’s paraphrase and traditional Old English poetic formula, that we have the canonical vernacular version studied today (Magoun, Jr. 57).

Manuscript Witnesses.

Fortunately, I had the opportunity to track the history of Caedmon’s Hymn by examining facsimiles of its different manuscript witnesses. I have included below a brief summary detailing my first encounter with facsimiles.

- “The Leningrad Bede” St. Petersburg, Russian National Library Lat. Q.v.I.18 [Gneuss 846]

- “The Moore Bede” Cambridge, University Library Kk.5.16 [Gneuss 25]

- “The Tanner Bede” Oxford Bodleian Library Tanner 10(9830) [Gneuss 668]

“The Leningrad Bede”

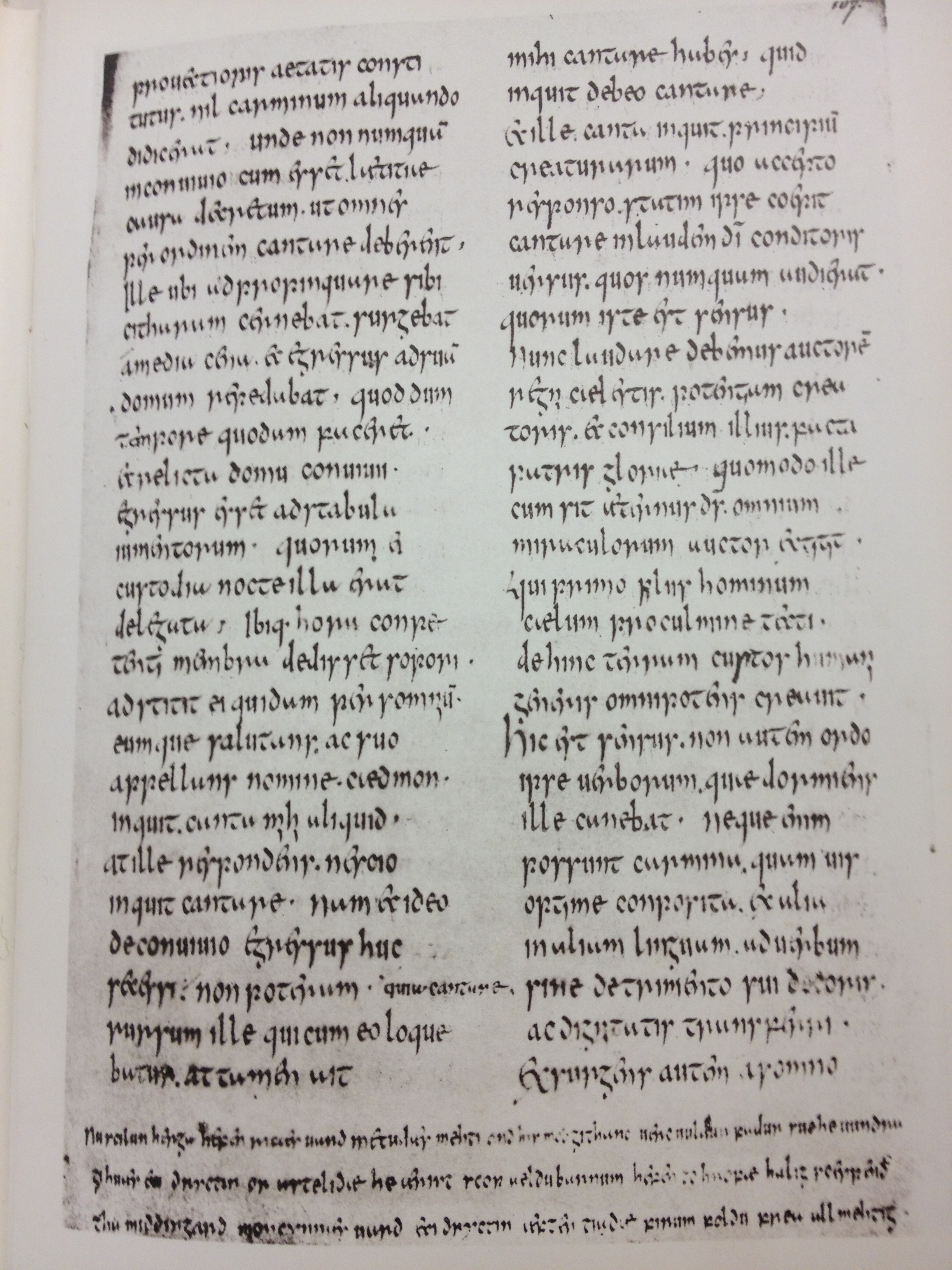

Looking first at the eighth century “Leningrad” witness, the Hymn appears as a marginal gloss on the bottom of the manuscript. On examining this manuscript I could clearly distinguish between the smaller grade insular used for the vernacular version of Caedmon’s Hymn and the larger grade insular minusculereserved for the central text.

Another important factor distinguishing the Latin and Vernacular versions is the layout. In the picture of the facsimile provided below one can clearly see that the vernacular translation runs in a continuous line across the bottom of the manuscript, while the central text above is laid out in separate columns.

“The Moore Bede”

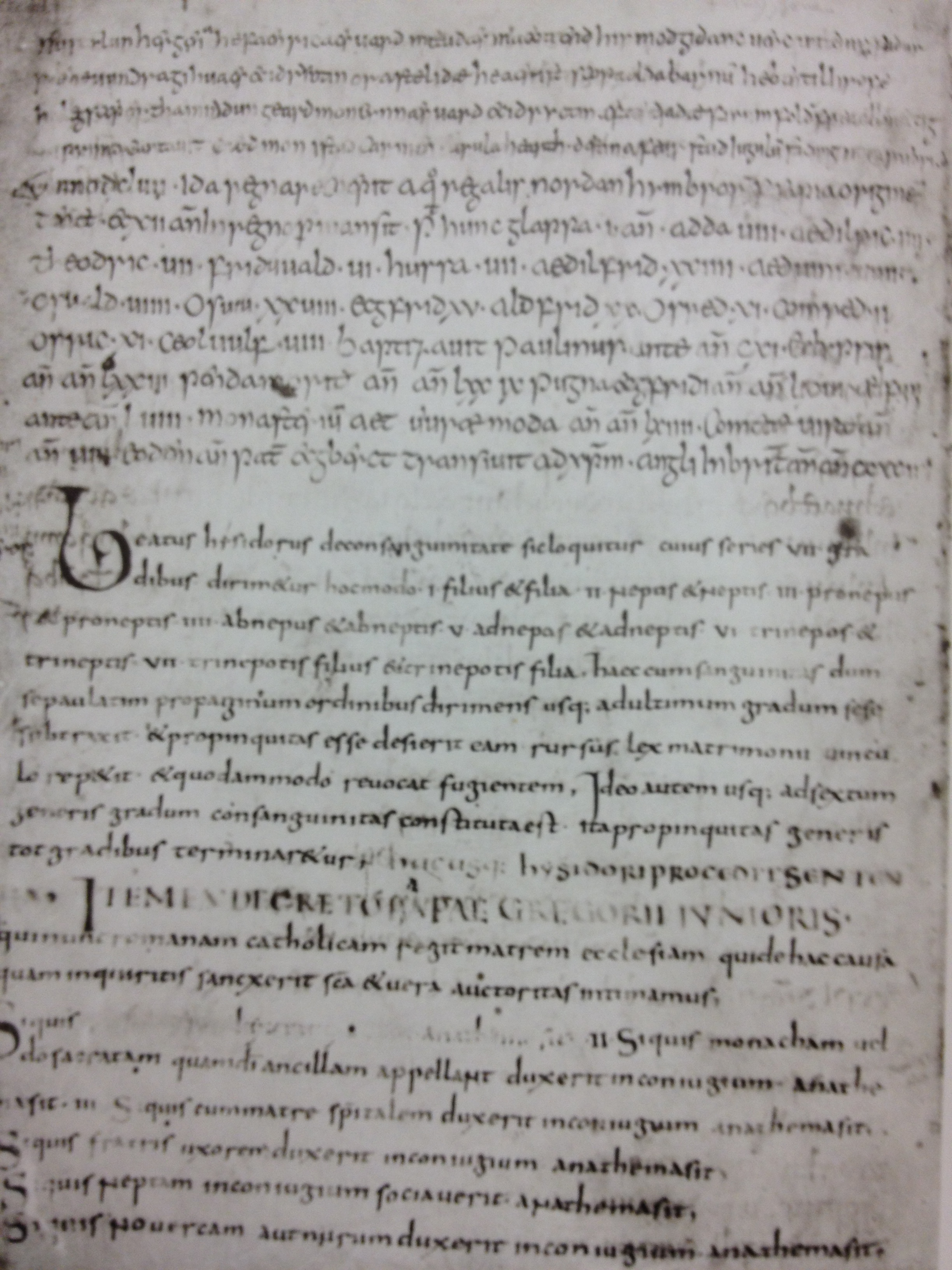

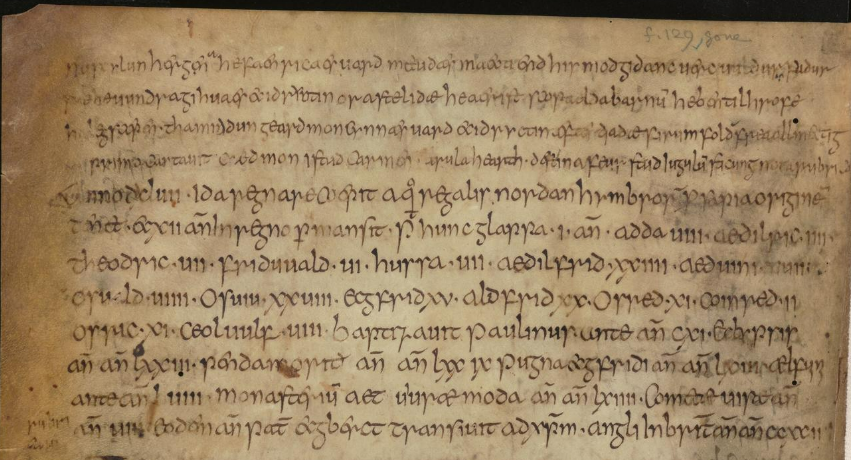

The second eighth century witness, “The Moore Bede”, shows the Hymn as marginal gloss on the top of the manuscript. I found it more difficult to distinguish between the vernacular version and the central text in this particular manuscript as it was in closer proximity to the central text.

From the picture below it’s clear that in this manuscript witness the layout of both the Latin and the vernacular incorporated the continuous line structure. In this instance distinguishing between the Latin and vernacular text would rely on my novice ability to either spot the different grades of insular minuscule, or to decipher the words before me until I found a familiar Old English word.

“The Tanner Bede”

The third manuscript witness dated from the early eleventh century and shows the vernacular version of Caedmon’s Hymn occupying its place of prominence as the central text of the manuscript. Now that Caedmon’s Hymn occupied the centre of the manuscript I found it more difficult to distinguish it apart from the surrounding text. In this particular manuscript witness there was no difference in terms of layout or grade of script to indicate the beginning of the Hymn; this time I had to read through the manuscript until I met the Hymn‘s famous opening word “Nu” before I could find it.

Conclusion

Studying the history of Caedmon’s Hymn through its manuscript witnesses offers a fascinating insight into the development of the English language. While examining these manuscripts I could clearly see how the vernacular language transitioned from the oral to the literary world, replacing the once canonical Latin paraphrase as the centre and designating the holy and powerful language of Latin to the margins English glosses once occupied.

Works Cited

Kiernan, Kevin S. “Reading Caedmon’s ‘Hymn’ with Someone Else’s Glosses.” Representations 32.3 (1990): 157–174. Print.

Magoun, Jr., Francis P. “Bede’s Story of Caedmon: The Case History of an Anglo-Saxon Oral Singer.” Speculum 30.1 (1955): 49–63. Print.

Shepherd, G. “The Propethic Caedmon.” The Review of English Studies 5.18 (1954): 113–122. Print. New Series.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

No Comments