The rationale for Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales is competition. The pilgrims must compete in a story competition where the winner of the competition gets their dinner bought for them and the remaining participants provide their own. This sense of competition resonates within the tales themselves, where each tale offers its own particular perspective and comes with its own inherent judgements.

In my study of The Canterbury Tales I found that this competition of perspectives was most pronounced in Chaucer’s juxtaposition of The Knyghtes Tale, a long romance tale with The Myllers Tale, essentially the rudest story of all the tales. The order of The Canterbury Tales is unfixed, except for the first two tales, The Knyghtes Tale and The Myllers Tale.

The Knyghtes Tale represents the high brow medieval literature circulating at the time and encompasses existential issues like chance and fate; while The Myllers Tale is a fabliau, that is to say a tale distinguished by its gritty realism and its black comical narrative. Chaucer doesn’t just simply give a romance and a rude story at the start of The Canterbury Tales (hereafter abbreviated to The Tales). By pairing The Myllers Tale immediately after The Knyghtes Tale Chaucer makes the genre of fabliau worthwhile by parodying the concerns that are expressed in The Knyghtes Tale, and in doing so, effectively provides the reader with two different perspectives in which to view the world.

The Knyghtes Tale is an intellectually ambitious narrative ruminating upon the big questions underlying human existence and vocalises humankind’s inquisitiveness concerning fate, destiny and the workings of God. Diametrically opposed to this existential viewpoint, The Myllers Tale undercuts these anxieties and depicts a world with no supernatural forces dictating who prospers and who fails. The world of The Myllers Tale is a world where an individual’s agency and wit (or lack) determine their fate and fortune.

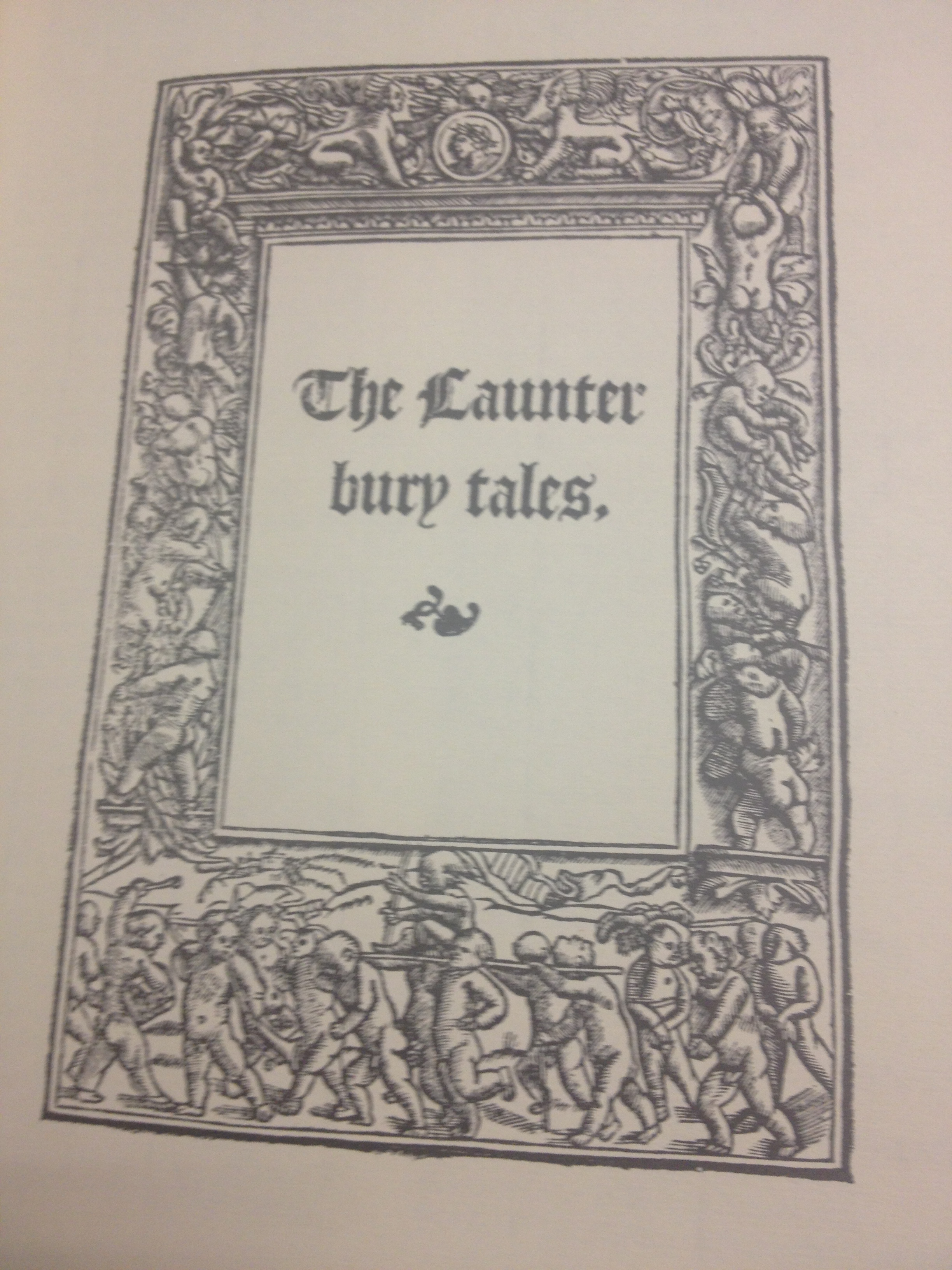

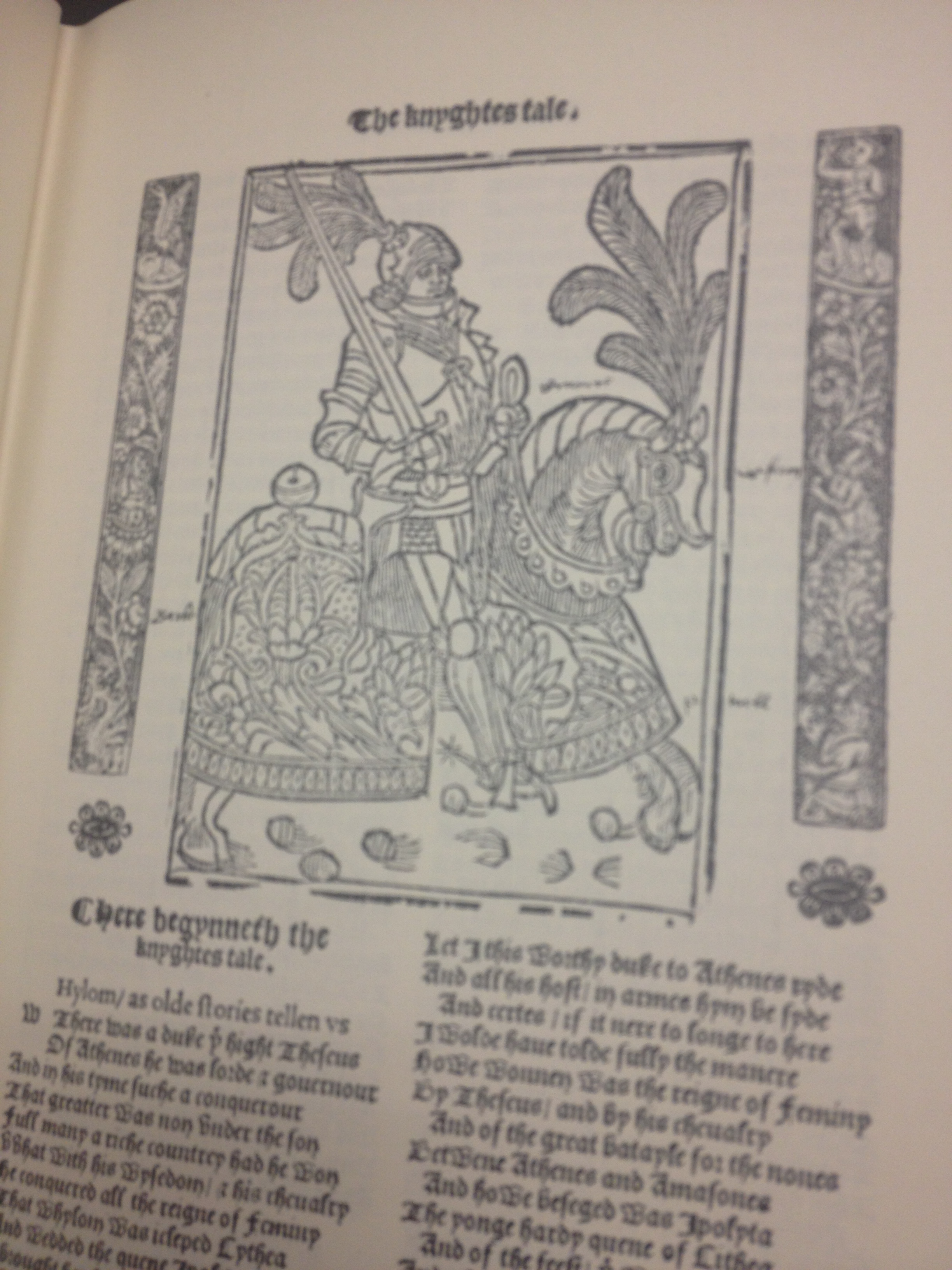

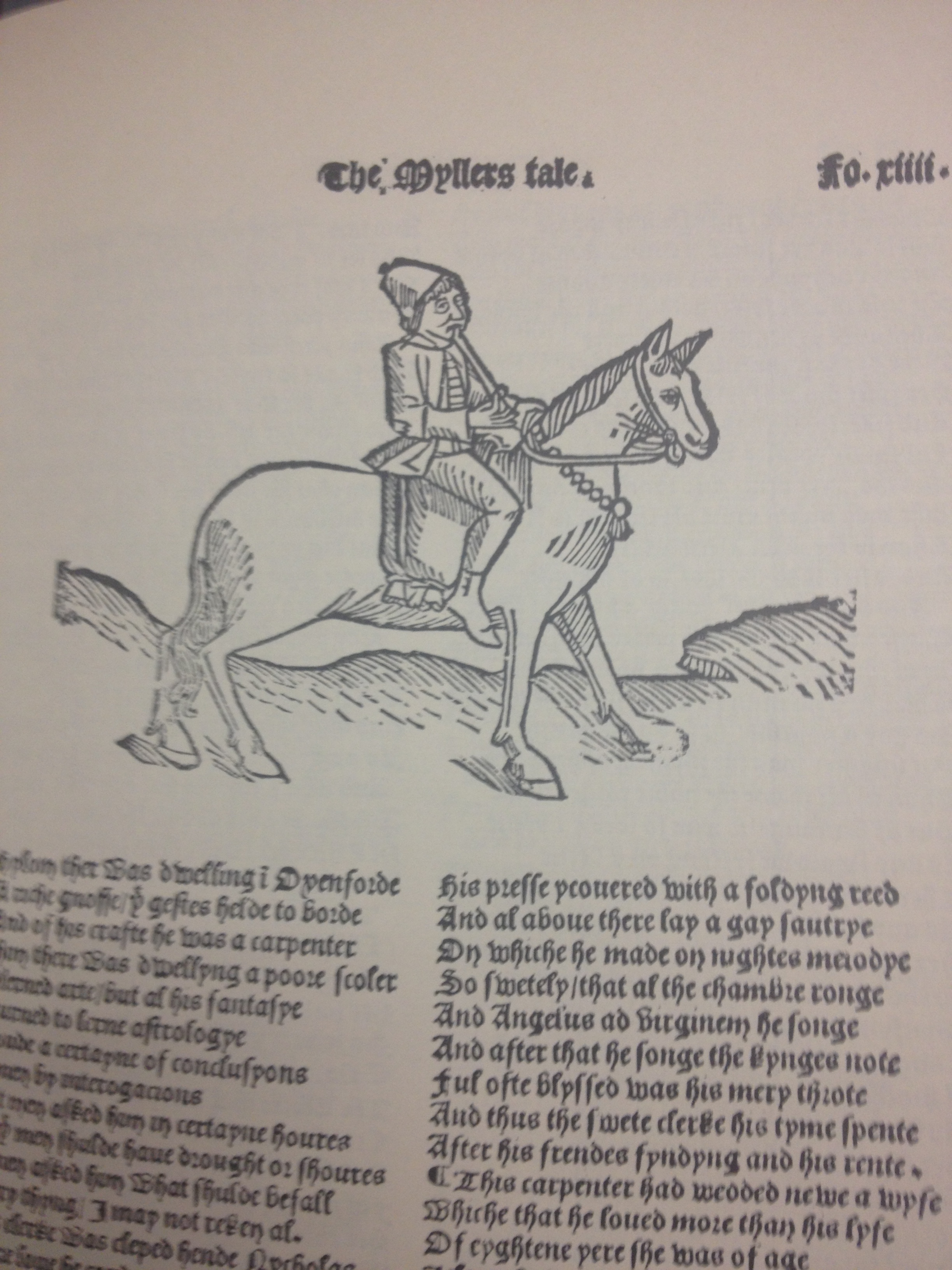

As part of my MA my fellow classmates and I were given a tour of the Special Collections and Rare Books Reading Room within UCC’s Boole Library. During this tour the Archivist had laid out Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Works 1532: With Supplementary Material from the editions of 1542, 1561, 1598, and 1602. I was intrigued with the illustrations that accompanied the Knyghtes and the Myllers tales in this book as they visually conveyed this juxtaposition.

This illustration represents a finely glad Knight upon his equally well dressed mount. This visually indicates both the Knight’s elevated social position amongst the other pilgrims and signifies that the story he will tell belongs to the upper echelons of medieval society.

In contrast to the first illustration, the above image that introduces the Myller’s Tale is reflective of the Miller’s own lowly social rank. Here the Miller is depicted in less fine attire than the Knight, presumably wearing clothes that would’ve been worn by peasants. Similarly the Miller’s horse looks nothing like the Knight’s handsome steed, rather it resembles an old, inferior work horse whose only adornments are its bridle and saddle. I felt that this visual depiction of the Miller complemented Chaucer’s work, particularly in respect to the Miller’s rude interruption in which he jumps the queue in the story competition.

Examining these illustrations in relation to their corresponding stories served enhanced the value of their context. Their context – that is both tales being fixed and juxtaposed together – complete Chaucer’s world outlook where spiritual concerns govern the world of the Knyghtes Tale, and the catalyst underlying the world of the Myllers Tale is the sexual appetite of its characters. To conclude neither the Knyghtes or the Myllers would have had the same resonance without each other.

Works Cited

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Works 1532: With Supplementary Material from the editions of 1542, 1561, 1598, and 1602. Yorkshire: Scholar Press, 1974. Print.

*The images included in this post are my own photographs taken of the above-mentioned source, with permission from Special Collections, Boole Library, University College Cork.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

No Comments