The Awntyrs Off Arthur (Awnytrs) is an Arthurian Romance written in Middle English hyper-alliterative verse which is the most demanding and richly echoic style of verse in the English language. Each stanza is comprised of thirteen lines, which each line features four alliterative stresses, and adhere to the rhyming scheme ababababcdddc. From the title I anticipated that the poem would centre on King Arthur and it opened as I expected by focusing on King Arthur and his court embarking on a deer hunt. The poem’s initial focus gives way and settles instead on Sir Gawain and describes two episodes that he is part of. The first half of the poem recounts Sir Gawain and Queen Guinevere’s ghostly encounter with her mother, while the second half of the poem delineates a land dispute that arises between Sir Gawain and Sir Galeron of Galloway. My response will be focused on the first half of the poem and in this post I will be ruminating upon certain intriguing aspects associated with this ghostly encounter.

The advent of Guinevere’s mother is described in Awntyrs as a phantasmagorical event: the hunt is abruptly stopped and the knights are plunged into darkness “The day wex als dirke/As hit were mydnight myrke” and they are forced to find shelter from the sudden stormy weather “Thay ranne faste to the roches, for reddoure of the raynne” (Awntyrs 75-76, 81). The approach of the ghost itself is described as a horrific and terror-inducing cacophony of “Yauland and yomerland, with many loude yelle/Hit yaules, hit yameres, with waymynges wete” (“Howling and wailing, with many a loud yell/It howls, it wails, with tearful lamentations”) (Awntyrs 86-87).

Reading the passage preceding the ghost’s arrival I was struck by the following sentence, “There come a lowe one the loughe” (“There appeared a fire in the lake”) (Awntyrs 83). My previous studies on the treatment of monstrosity and monstrous landscapes within early and medieval English texts focused on a similar description within the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, “There every night a dire portent can be seen, fire on the flood”(Fulk 177). In the poem Beowulf this convergence of two disparate elements, fire and water, shroud the landscape in the “uncanny” and create a liminal landscape in which both Grendel and his mother could exist. Similarly, the combination of the gothic overtones and the “dire portent” or unnatural union between fire and water in Awntyrs associates the landscape Guinevere’s mother inhabits with the “uncanny” and effectively highlights and augments her monstrous or supernatural qualities.

The approach and appearance of Guinevere’s mother offer significant insights into the medieval perception of the afterlife. The ghost of Awntyrs does not descend from heaven, rather she is described as gliding towards Sir Gawain and Guinevere from the lake. The horizontal approach of the ghost is important because it symbolises her spiritual punishment, the inability to transcend this earthly realm, as a result of her sins “That is luf paramour, listes and delites/That has me light and laft logh in a lake” ([The cause] is sexual love, pleasure and delight/ That has brought me low and left me deep in a lake”) (Awntyrs 213-214). Her inability to transcend is reinforced by the ghost’s corporeal appearance which differs from modern connotations of ghost as ethereal beings.

In contrast to the incorporeal connotations the graphic passage which describes the ghost in Awntyrs is literally more grounded, in that it shares striking similarities with a decomposing corpse:

- “Bare was the body and blak to the bone,/Al biclagged in clay uncomly cladde.” (“The body was bare and black to the bone, foully covered all [over] with clotted earth”) (Awntyrs 105-106).

- “But on hide ne on huwe no heling hit hadde” (“But it had no skin no complexion no cover”) (Awntyrs 108).

- “With eighen holked ful holle” (“With sunken, hollow eyes”) (Awntyrs 116).

The above description not only conveys the physical degradation associated with death but equally acts as a “Memento Mori” (Remember that you will die”), a symbolic reminder of the inevitability of death and a lesson on the decomposing power of sin. The ambiguity in the language referring to Guinevere’s mother as a body and a “goste” inspired this post because I felt it evoked the sense of an ambiguous afterlife (Awntyrs 325). Her horizontal approach and her rotting corpse both strongly signify that Guinevere’s mother’s soul is still rooted in the land of the living.

Works Cited

Fulk, R.D., ed. The Beowulf Manuscript. Trans. R.D. Fulk. London: Harvard University Press, 2010. Print.

Hahn, T. ed. “The Awntyrs Off Arthur.” TEAMS Middle English Text Series. N. p., n.d. Web. 20 Feb 2014.

Images Cited

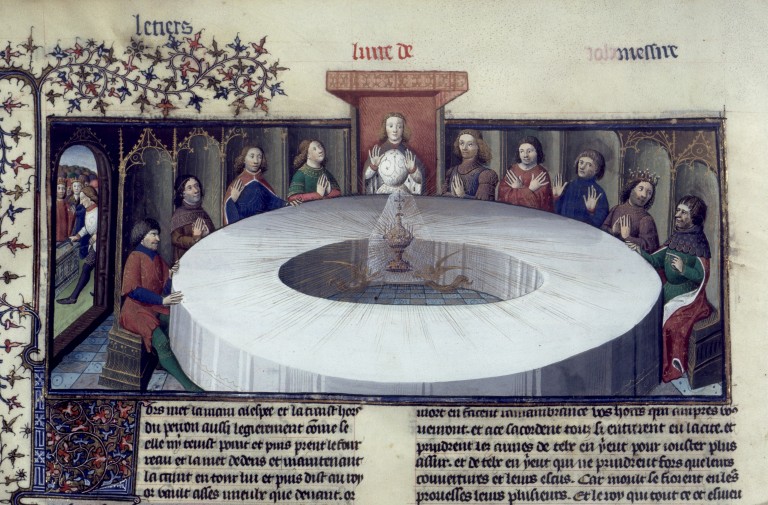

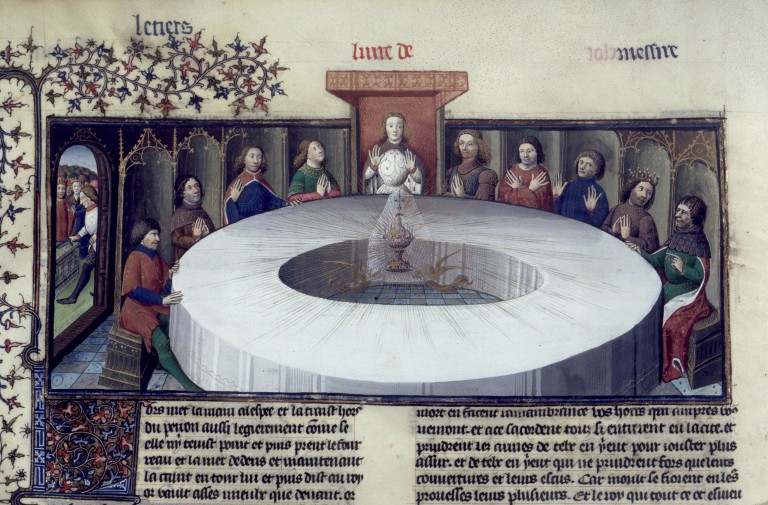

Apparition Saint Graal. Scanned reproduction of a fifteenth century French Manuscript. 2006. King Arthur. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 20 Feb. 2014.

“The Ghostbusters Logo”. An Adobe illustration of the Ghostbusters logo. Ghostbusters (franchise). Wikimedia Commons. Web. 20 Feb. 2014.

Krapp, Alexander P. Wadling. Photograph. 2006. The Awntyrs off Arthure. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 20 Feb. 2014.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight from Pearl Manuscript. Illustration from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight from the late fourteenth century Pearl Manuscript (Cotton Nero A. x) in the British Library. 2012. King Arthur. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 20 Feb. 2014.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

No Comments