Introduction

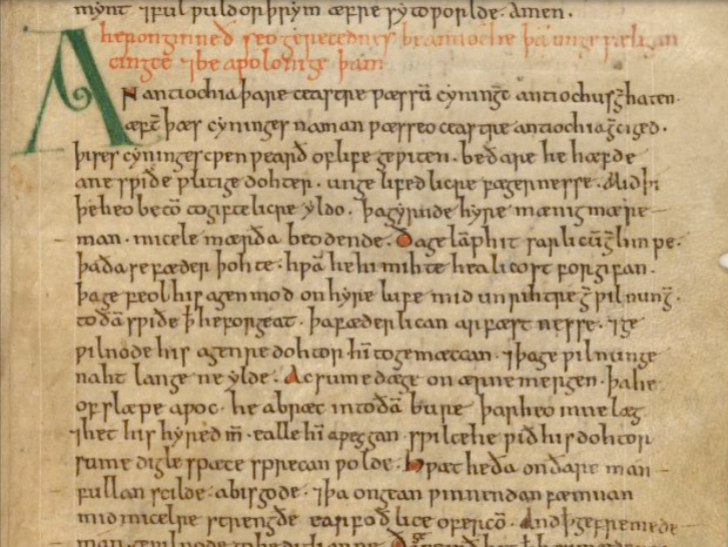

The prosaic Old English Apollonius of Tyre occurs in the manuscript Cambridge Corpus Christi College 201(CCCC201). This single manuscript is predominantly comprised of religious, secular, poetic material, and the inclusion of Apollonius in this context has occasioned a considerable degree of confusion in relation to its genre classification, and the rationale behind the compiler’s decision to include Apollonius within this manuscript.

Miscellany

This ambiguity becomes clear when you look at CCCC 201 in its entirety; where it becomes quickly apparent that CCCC 201 is principally known for its considerable connection to Archbishop Wulfstan with the majority of its material being associated with him. The Wulfstanian material comprises of a number of Wulfstan’s homilies as well as anonymous homilies that have been ascribed to him because of their stylistic similarity; pastoral letters; sections from his Institutes of Polity; his Canons of Edgar and the Northumbrian Priests’ Law (which is another example of a text of uncertain authorship that is affiliated with Wulfstan). Two particular law codes, those belonging to Æthelræd and Cnut, also adhere to this manuscript’s prevalent Wulfstanian style and are interspersed with the remaining law codes belonging to Eadgar, Eadmund and Æthelstan that are characteristically non- Wulfstanian in manner.

Apart from the material attributed to Wulfstan, CCCC 201 contains rare religious material, in the form of the penitential and confessional literature it preserves in the vernacular, the most noteworthy of which is the “Late Old English Handbook for the Use of a Confessor”, which is the longest example of penitential literature to date. Within this religious milieu CCCC 201 also features two Old English texts dealing with English saints and their burial places and a vernacular version of a biblical account of The Story of Joseph.

To complete the diverse ensemble that is CCCC 201 there are also five Old English poems: Judgement Day II; Exhortation to Christian Living; Summons to Prayers; Lord’s Prayer II and Gloria I. The manuscript concludes with Latin forms that deal with absolution and confession (Heyworth 2).

How Does Apollonius Fit?

A cursory glance at the overall compilation of CCCC 201 throws Apollonius in stark relief against what has been classified by Patrick Wormald as a “Wulstanian primer of Christian standards” (Wormald 208–209). In light of Apollonius being defined by Clare Lees’ as “the first heterosexual love narrative in English” and considered the earliest extant example of romantic literature in the vernacular; this ambiguity has inspired a desire to justify the presence of Apollonius within such a framework by endeavouring to reconcile it with its contiguous material (Lees 18).

Within the manuscript Apollonius is preceded by the “Handbook for the Use of a Confessor”, a number of law codes specifically I Cnut, II Cnut, VI Æthelræd, and Wulfstan’s Institutes of Polity and it is followed by the hagiographical vernacular accounts of English saints and their resting places (Heyworth 3; Salvador-Bello 750).

Hagiography

Traditionally Apollonius’s presence within CCCC 201 has been explicated by its affinity to hagiography. Placing Apollonius in this genre succinctly provides a connection between the ambiguous Apollonius, The Story of Joseph and the pursuing vernacular “English Saints” and their “Burial Places” that illustrate a strong hagiographic influence (Salvador-Bello 752). Associating Apollonius with this genre encourages the text to be read as a “moral exemplum for a clerical audience” (Salvador-Bello 750).

Exemplum

Reading Apollonius as an exemplum for an ecclesiastical audience is supported by the translator’s deliberate manipulation of its Latin source Historia Apollonii Regis Tyri in order to emphasis Apollonius’ exemplary generosity and humility: “Indeed then Apollonius cast off his noble status and took there the name of a merchant rather than a benefactor, and that price which he took for the wheat he immediately gave back again to benefit the city” (Salvador-Bello 756; Treharne 283). While the translator asserts Apollonius’ ideal moral qualities, Melanie Heyworth argues it is the text’s examination on the subject of marital morality which reconciles Corpus 201’s seemingly incongruent compilation (Heyworth 6).

Incest

The vernacular version of Apollonius manipulates the translation of the Historia from the very beginning by expanding upon the title to make explicit reference to “þam ungesæligan cingce” “the wicked king” (Treharne 276–277). The fact that the incipit has been deliberately manipulated and highlighted in rubric indicates the significant feature incest plays in the text and simultaneously serves to condemn Antiochus as evil and wicked for being the instigator: “he fell in love with her [his daughter] in his own mind with illegal desire, in such as way that he forgot the duty proper to a father and desired his own daughter as a wife” (Treharne 277). The significance of the opening incest episode takes precedence over Apollonius’s moral character when it’s placed within its manuscript context.

“Rightful” or Lawful Marriage

When read within its larger MS context can Apollonius be read as a text that’s part of a collective authority speaking out against inappropriate marital relations? Looking at the law codes first in the I Cnut chapter seven, it makes reference to the prohibition against close marriages: “and we teach and we command and in the name of God enjoin that no Christian man ever take a wife from his own kindred within six degrees of relationship, nor the widow of his kinsman, who was closely related to him” (qtd. in Heyworth 10)*.

The Northumbrian Priests’ Law supports this proscription by highlighting the illegality of certain marriage practices “that any man should marry a nearly related person, (any nearer) than outside the fourth degree. And no man is to marry anyone spiritually related to him. And if he does so, may he not have God’s mercy, unless he desists and atones as the bishop directs” (qtd. in Heyworth 10)*.

Conclusion

The ambiguous nature of Apollonius of Tyre and its ability to shift in and out of genres: traditionally belonging to hagiography – but the presence of incest problematises this reading; recognised as the genesis of English romance literature – yet its hagiographical affinities serve to designate Apollonius as a hybrid literary genre such as hagiographical romance or proto romance. This crisis of genre classification is reflective of our modern compulsion to unify and compartmentalise texts. When considering a manuscript as diverse as Cambridge Corpus Christi College 201, it’s important to note that Anglo Saxon compilers may not have shared our present preoccupation and perhaps possessed a different rationale. A rationale that remains elusive “if a text is detached from its codicological environment…[because]…we risk losing that part of its meaning” (Heyworth 5).

Notes

*The translation of King Cnut’s law code that I quoted is from Heyworth’s article but is originally from A.G. Kennedy’s edition “Cnut’s Law Code of 1018”, Anglo-Saxon England 11 (1983): 57-83. Print.

*The translation of the law code referenced from the Northumbrian Priests’ Law was sourced by Heyworth from English Historical Documents: I, c. 500-1042, trans. Dorothy Whitelock, Second Edition. (London: Methuen, 1979), 471-72. (Whitelock 471–72.

Works Cited

Heyworth, Maria. “Apollonius of Tyre in Its Manuscript Context: An Issue of Marriage.” Philological Quarterly 86.1 (1997): 1–26. Print.

Lees, Clare A. “Engendering Religious Desire: Sex, Knowledge, and Christian Identity in Anglo-Saxon England.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 1.27 (1997): 17–46. Print.

Salvador-Bello, Mercedes. “The Old English ‘Apollonius of Tyre’ in the Light of Early Romance Tradition: An Assessment of Its Plot and Charaterisation in Relation to Marie de France’s ‘Eliduc.’” English Studies 7.93 (2012): 749–774. Print.

Treharne, Elaine, ed. Old and Middle English c.890 – c.1400: An Anthology. Second Edition. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004. Print.

Wormald, Patrick. The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century, Vol. 1: Legislation and Its Limits. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. Print.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

No Comments