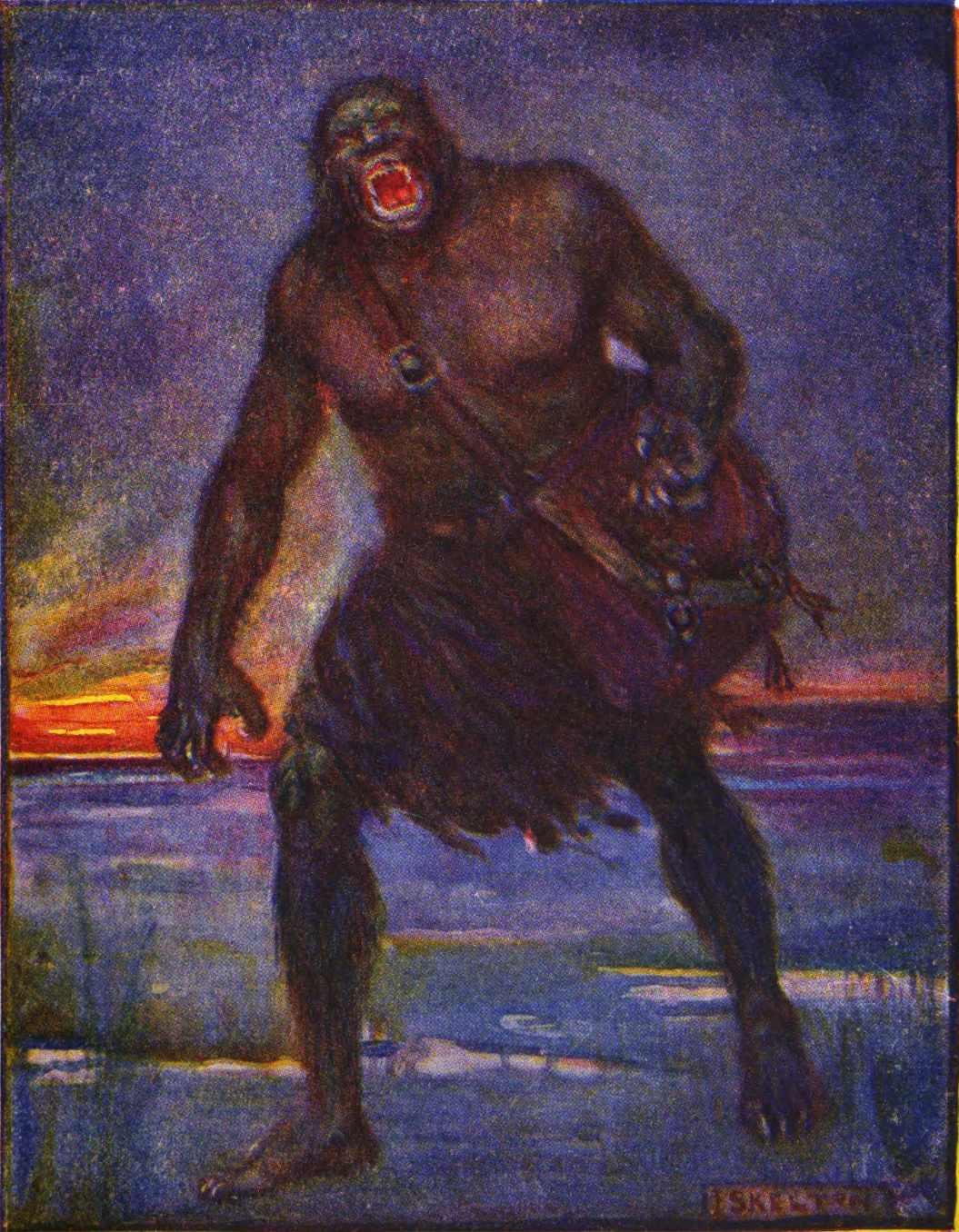

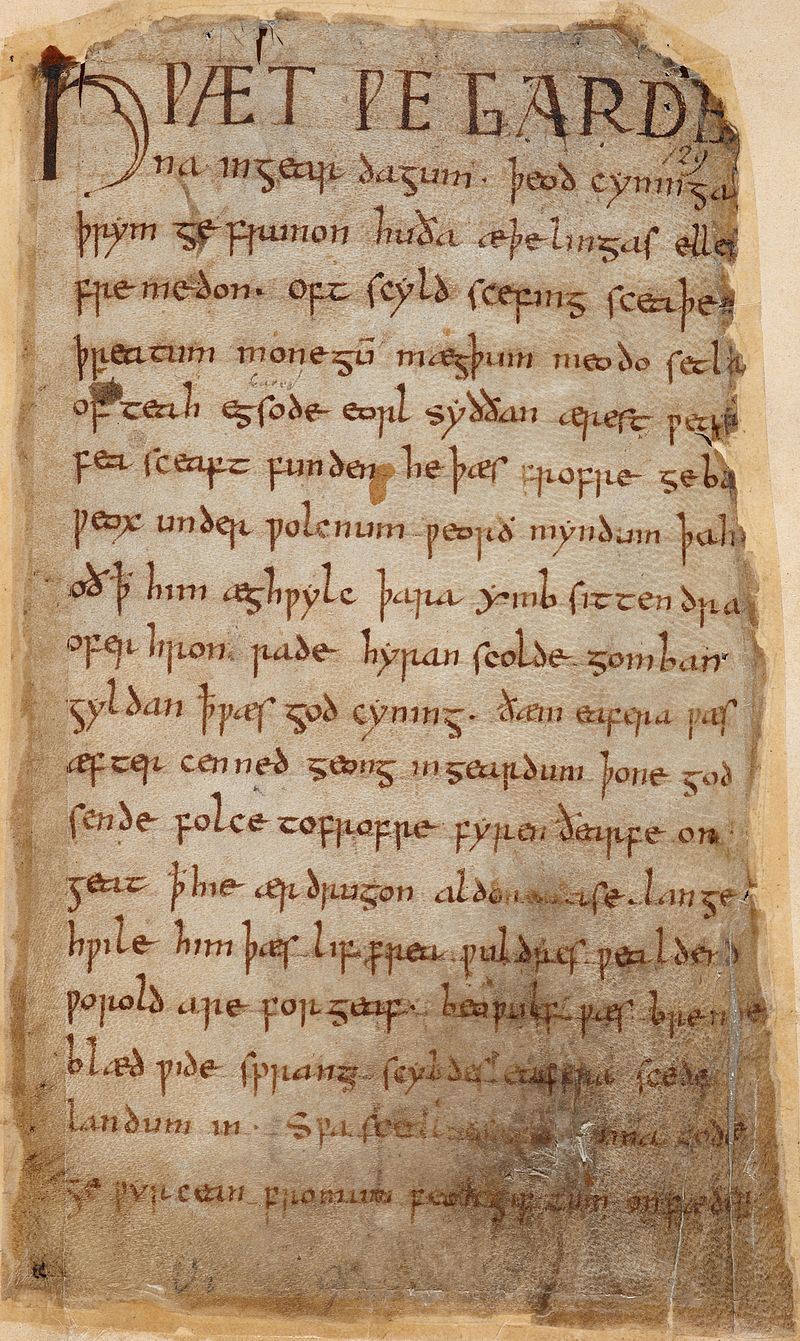

The term “liminal” is derived from the Latin word “limen” meaning doorway or threshold. Originally used as an anthropological term by Victor Turner the term refers to that which is transitional or in between states (Ashley). Its later application to literature and to art is intrinsically linked to its function of providing a safe space for cultural release, in the ambiguous figure of the monster. In a world dominated by hostility and darkness the bodies of Grendel and Glámr provided safe spaces to express the customs and practices that were forbidden and prohibited within their respective societies. In this instance Bahktin advocated that the monster provided a liberation of all that was repressed or according to Cohen’s postulate “fear of the monster was really a kind of desire”; where the fantasies of aggression and inversion could be acted out through Grendel and Glámr’s harmful actions, yet were securely contained within the permanently liminal space that is the monster’s body (Cohen).

The ability of both Grendel and Glámr to provide this release is due to their betwixt and between nature (Ashley). The character Glámr for instance was described as being asocial and a loner and in death he returns as a restless draugr, which essentially is a physically active dead being. Glámr as a draugr crosses the set boundaries of the natural world, or the ‘limen’ or ‘threshold’ dividing life and death (Byock 32). Similarly Grendel a “ an-genga” loner like Glámr is so ambiguously described that he is shrouded in the mystery of the abject and the uncanny (Fulk 114). Grendel is simultaneously described as a corporeal being of great strength and as a “scriðan sceadu-genga” (a shadow walker creeping) or as “deorc deaþ-scua” (death’s dark shadow) (Fulk 132, 96). Glámr’s liminal stance as a dead person with the semblance of life and the pervasive mysterious aspect of Grendel’s character, mean that both monsters are no longer restrained by the bonds of society and are therefore capable of acting out the fantasies of aggression that no human character could effectively do.

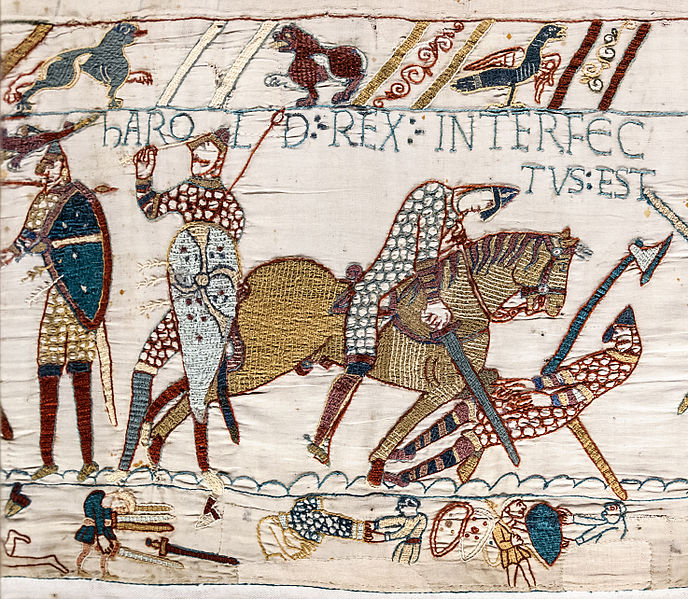

The ambiguous nature of the monster’s body allows them to “elude and slip through the network of classification” that defines our society and so they are excluded and left to decorate the margins of society, much like they decorated the margins of The Bayeux Tapestry or the Hereford Map (Ashley). The monsters inhabit the margins of our cultural space, the uninhabited and wild regions. In Beowulf Grendel “hæðstapa” and his mother are described as inhabiting “dygel lond”, a hidden or secret country, showing clearly how this space is not yet cultivated by civilization and is therefore beyond the borders of human knowledge (Fulk 176, 174). Surprisingly it’s not just that which is monstrous that occupies the liminal or marginal zones. As Mittman asserts both heroes and saints were conjoined with monstrosity in their decision to inhabit the dangerous or repellent zones like the fens (Mittman). Unlike Grendel the poems Guthlac A and Guthlac B show how Guthlac chose to voluntarily exclude himself from civilization by locating himself within the civilized and uninhabited geographical periphery: “he started inhabiting, alone, a hilly dwelling place” (Treharne). While Grendel and Glámr showed their ability to provide a release of that which is repressed for the good of society, Guthlac’s asceticism demonstrates the release that can be found by obtaining fresh perspectives when separated from society.

Photograph taken by Malene Thyssen.

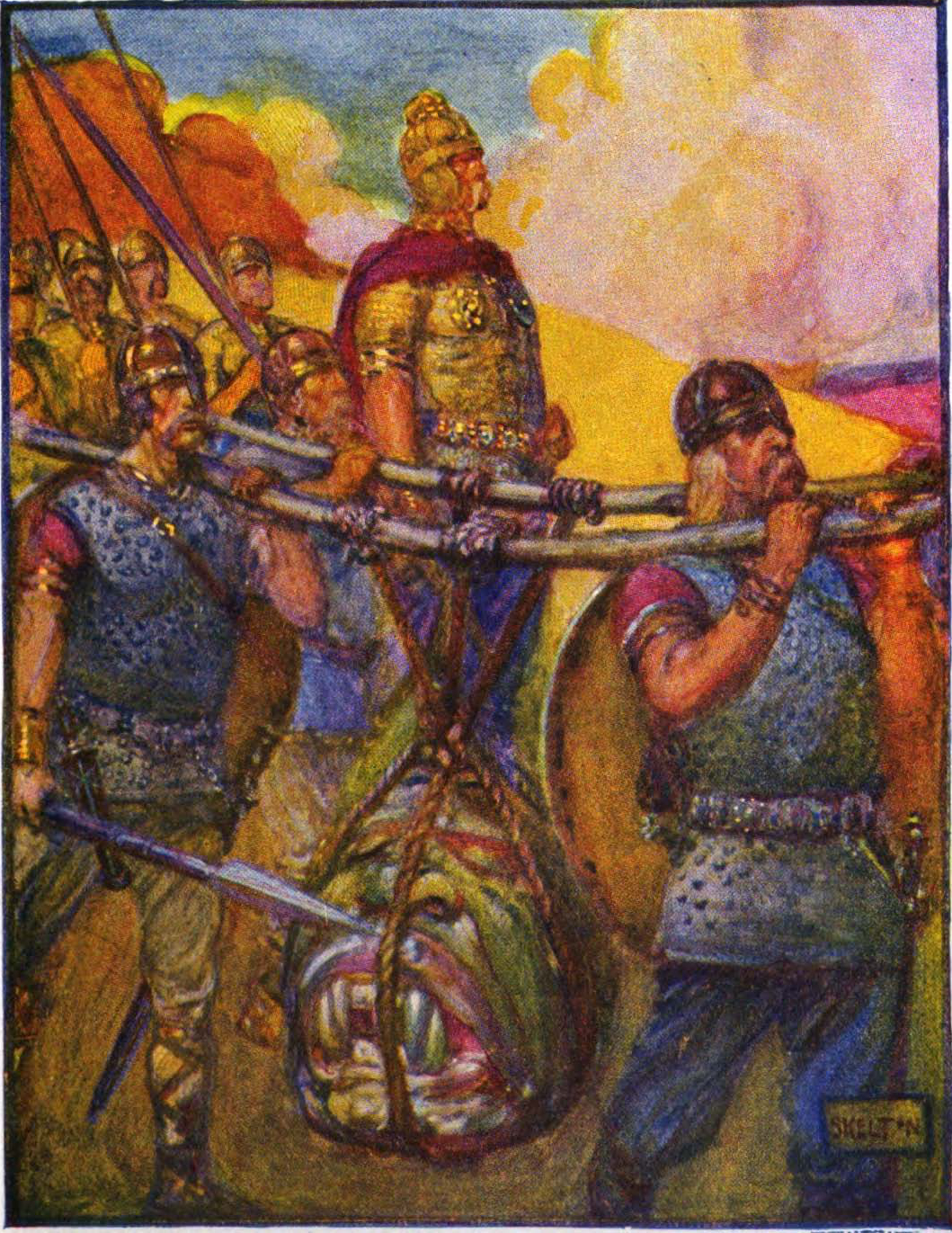

More significant than their marginal locations is the visits paid by Grendel and Glámr to the Heorot or Thorhallsstead. Taking the halls as a social and cultural microcosm for civilization, the menacing crossing of both Grendel and Glámr over these thresholds are symbolic of how monsters function as “Harbingers of Catergory Crises” by smashing the distinctions separating the included from the excluded (Cohen). Glámr and Grettir’s struggle in Thorshallsstead is particularly symbolic as it shows that in Grettir’s success in thrusting Glámr outside the doorway, he falls out with him; falling from the social hub of human society, into the exile and exclusion designated to the realm of the monstrous. Sayers asserts that the root of Grettir’s true terror of Glámr’s gaze is the possession of knowledge from the other side and how it signifies the start of his descent from ambiguous hero to ambiguous monster (Sayers).

The relevance of heroes to liminality is due to the fact that their existence is contingent on monsters. Like monsters, the heroes Beowulf and Grettir are separated from other men because of their excessive size and strength. We are told that Beowulf was the strongest of all men living at that time and that Grendal had never met with a “mund-griþe maran” (Fulk 134). The distinguishing factor between the hero and the monster is the hero’s ability to use his excessive strength in the service of those weaker than himself. Both Grettir and Beowulf define themselves as professional heroes that augment their career by going out to the “frecne stow” and “æl-wihta eard” and encountering the monsters (Fulk 176, 184). Without Grendel and Glámr and the smörgåsbord of monsters the hero has no socially acceptable forum for his power and therefore no other role that society would deem valuable.

Despite being conceptually and geographically marginalized to the peripheries of the mind and society the monsters of liminality always return and infiltrate the centre of civilization, because they are “fundamentally essential” to our understanding of our own ambiguous human nature (Tolkien 261).

Works Cited

Ashley, Kathleen M., ed. Victor Turner and The Construction of Cultural Criticism: Between Literature and Anthropology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990. Print.

Byock, Jesse, trans. Grettir’s Saga. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. Print.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome, ed. Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996. Print.

Fulk, R.D., ed. The Beowulf Manuscript. Trans. R.D. Fulk. London: Harvard University Press, 2010. Print.

Mittman, Asa Simon. Maps and Monsters in Medieval England. New York: Routledge, 2006. Print.

Sayers, William. “The Alien and Alienated as Unquiet Dead in the Sagas of the Icelanders.” Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996. Print.

Tolkien, J.R.R. Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics. London: Oxford University Press, 1936. Print.

Treharne, Elaine, ed. Old and Middle English c.890 – c.1400: An Anthology. Second Edition. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004. Print.

Images Cited

Myrabella. “The Bayeux Tapestry – Scene 57: The Death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings”. Photograph. 2007. Bayeux Tapestry. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 03 Nov. 2013.

Skelton, J.R. Stories of Beowulf. “Grendel”. 1908 Illustration. 2010. Grendel. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 03 Nov. 2013.

Skelton, J. R. Stories of Beowulf. “Carrying Grendel’s head”. 1908 Illustration. 2010. Children’s Book Illustration. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 03 Nov. 2013.

Thyssen, Malene. Fyrkat Hus Stor. Photograph. 2002. Mead Hall. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 03 Nov. 2013.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

No Comments